Rejuvenating Your Assessments with Student-Friendly Rubrics

How a few simple tweaks to my rubric led to faster grading and better feedback.

“In the real world, many teenagers don’t read the rubric at all. Or if they do, they aren’t sure what to do with it. It’s my job to teach them.”

I had just finished grading my students’ projects, and I was exasperated. The projects were terrible. Not only did kids not demonstrate mastery of the communication objectives, in many cases they didn’t even complete the basic project requirements. This, despite my intentional communication. I had given kids a detailed, bulleted rubric when I assigned the project, and again when they turned their project in. I clearly outlined the project requirements; items like “Write a full paragraph (5 sentences) about each prompt”, “Include at least 3 examples of negation” and “Use accurate adjective agreement”. Yet, even my good students missed clearly stated objectives.

I returned my project feedback. Some kids briefly looked at their grades, then wadded up their feedback forms. Others shouted out their grades, asked each other, “What’d you get?”, or shoved their rubrics into their backpacks. Most kids didn’t seem to care at all about my carefully crafted feedback. One student, however, did approach me and ask, “Why did I get a C?”.

“Well, let’s look at the rubric,” I began helpfully. “Look here. You didn’t include a single example of negation.”

“What’s negation?” she asked.

And that, dear readers, was my moment of peak frustration! HOW could she not know what negation is, after all my careful instruction? And WHY would ANYONE turn in a project without knowing the terminology on the rubric?

The answer is pretty simple: my students didn’t really use the rubric.

And, that was largely my fault.

Now, I don’t mean to absolve students of their responsibility here. Students could - and probably should - take the time to evaluate their own work against the stated standard. Of course, that’s in a perfect world. In the real world, many teenagers don’t read the rubric at all. Or if they do, they aren’t sure what to do with it. It’s my job to teach them.

Reinventing My Rubrics

I took a hard look at my rubrics. I realized that, while clear to me, they were full of educational jargon, technical language, and fine print which many students treated like software user agreements: they checked the blocks as quickly as possible without really absorbing any content. Reinventing my rubrics to be student friendly was the first step in improving my assessment practices.

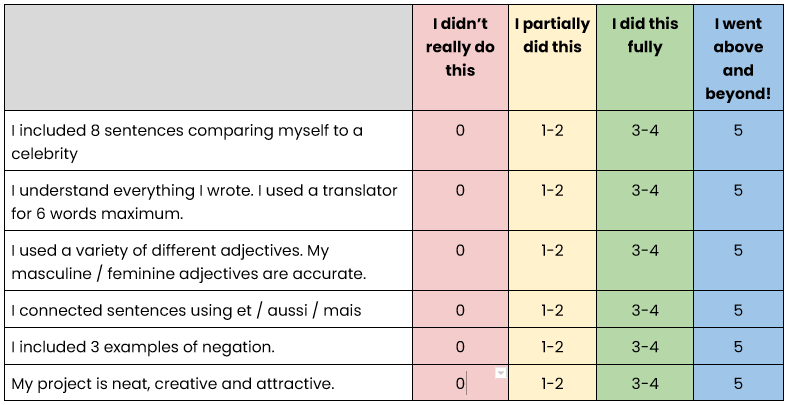

I simplified the rubric language and changed everything to “I statements”.

I included all the required elements.

I have at least 3 examples of negation using ne...pas

My adjectives agree, and I used a variety of different adjectives.

I stretched to use French creatively. I did not get outside help from a translator or another student

Next, I tackled the grading scale. The categories “Poor / fair / good / excellent” became:

I didn’t really do this (0 points)

I partially did this (1-2 points)

I did a good job on this (3-4 points)

I went above and beyond (5 points)

At the bottom of the rubric, I added reflection prompts such as, “Explain any above and beyond ratings here.” “What are you most proud of in this project?” “What will you do even better next time?”

Example of a student-friendly rubric.

Teaching Students to Use Rubrics

Using student-friendly language was a good first step, but it was useless if my students didn’t even read the rubrics. I had good reason for concern. In an informal show of hands, over half of my 8th grade students admitted they had never read the rubrics on prior French projects

I was incredulous. “Don’t your other teachers give you project rubrics?”

“They do,” an outspoken student shrugged. “But I don’t look at them.”

“Over half of my 8th grade students admitted they had never read the rubrics on prior French projects.”

I realized my students needed guidance and practice in assessing their own work against a standard. So, the next time we did a project, I adjusted my entire assessment approach. Like always, I shared my (new, student-friendly) rubric with kids at the beginning of the project. On the day the project was due, however, I didn’t just collect students’ work. Instead, I handed students a blank project rubric. We read through the possible scores, and then I asked each student to rate their own project on their rubric.

I told kids, “When I grade your project, the first thing I’ll do is look at how you rated yourself. Then I’ll check your project and see if I agree with you. If so, that will be your grade! If not, I’ll note on the rubric exactly why.”

Next, I had kids work with partners. “Show your partner your project, and explain why you gave yourself each rating. If you included three examples of negation, show where. If your project uses language creatively, point it out. Justify your score based on evidence.”

Finally, I asked my students to write a sentence or two explaining their rating. Students attached this page to the front of their projects and turned them in.

The impact: faster grading and better feedback.

My hope was that this process would help my students use and understand how to assess their work with some objectivity, and I was pleased with the results. What I didn’t anticipate was how much this would improve my own feedback to students, and how much it would speed up my project grading.

For me, one of the most time consuming aspects of grading is dithering over kids who are on the line between two ratings. I study, review, second guess myself… Having students hand in a completed rubric mitigated a lot of this. I found myself thinking things like:

“I didn’t anticipate how much effective self-evaluation would improve my own feedback to students, and how much it would speed up my grading. ”

Hmm. I’m not sure whether this is a 3 or a 4. You gave yourself a 3? Sounds good. I won’t argue that.

Oh, you REALIZED you didn’t complete that requirement? Great. Now I don’t feel bad about giving you a 0.

Wow, I hadn’t considered x, but the student really did push themself to do that. This project is creative in a way I wasn’t really thinking about!

Looking at kids’ self-evaluations also tipped me off on what to look for as I reviewed students’ work. And, often, the student identified items I would have written about, so all I wrote was “I agree”.

Sometimes, I disagreed with a student’s assessment. Writing a reply to their self-assessment was more personalized than the comments I used to write. The rubric became almost a conversation between me and the student, and students started reading it. After truly assessing their own work, they were invested in my response. My feedback became a lot more useful.

Changing my Instruction

These changes in my rubrics led to broader improvements in my practice. I started taking class time to have students evaluate sample work against rubrics I provided. I also revised my retake policy. Read about these steps, and their impact on students in my blog post on “Feedback and Self Evaluation”